Opportunity Culture Audio

Opportunity Culture Audio

#8. Dramatic Student Growth Follows Focus on Data, Small-Group Tutoring, and Collaboration

Lucama Elementary, a rural, Title I school in Wilson County, North Carolina, implemented several Opportunity Culture roles in 2021–22. Following a focus on data-driven, small-group tutoring, instruction based on the science of reading, and greater educator collaboration through Multi-Classroom Leader teams, the school dramatically increased student learning growth. Principal April Shackleford and Lucama educators explain their success, and why it led them in 2022 to expand to schoolwide Opportunity Culture roles.

April Shackleford: We had such a great student outcome and teacher impact in the three grade levels where we had Opportunity Culture last year, so in year two we went schoolwide.

SHARON KEBSCHULL BARRETT: I’m Sharon Kebschull Barrett, and this is Opportunity Culture Audio.

Walk into Lucama Elementary in Wilson County, North Carolina, and the vibe quickly becomes clear: This is a school buzzing with determination to form strong student bonds and make great learning gains.

When April Shackleford became its principal at the beginning of the 2021–22 school year, Lucama already had plans set for its first year of Opportunity Culture implementation, with two Multi-Classroom Leader teams—one for kindergarten and another for fourth and fifth grade, supported by an advanced paraprofessional known as a reach associate.

Having worked as a coach for beginning teachers through an East Carolina University program, Principal Shackleford loved the Opportunity Culture concept, in which teachers on a Multi-Classroom Leader’s team get deep support.

APRIL SHACKLEFORD: So I was ecstatic about it—I was excited about it because I know that if you have the right people in place, that’s when programs are powerful, and that’s when students and teachers make impact.

BARRETT: Lucama, with just over 350 students, is a rural, Title I school, but not, Shackleford said, a struggling school. The previous principal, Zachary Marks, had been moving Lucama in the right direction before Shackleford arrived, with the school having moved from a state-issued “C” grade to a “B” before Covid hit, after several years of failing to meet student growth expectations.

SHACKLEFORD: This is not a school that was what I would say struggling. This is a school that needed just a kick—and all we had to do was come together with one vision and see that we had to pass the torch each year. And so, what we did last year was—at the first semester of pushing out Opportunity Culture—was we clarified the roles of our team; we made sure that we were trying all of our instructional strategies reaching students.

BARRETT: Under Shackleford’s leadership, the school focuses hard on student data, and the two Multi-Classroom Leaders’ teams began showing rapid student growth by using that data to quickly adjust instruction. Shackleford happily brags about her students’ and teachers’ results on the end-of-the-year North Carolina tests.

SHACKLEFORD: In our state, in order to exceed growth, you have to be 2.0—our growth was 9.57 in one year, in 10 months following a pandemic! Our school letter grade went from a 71 prior to the pandemic to an 83. We are just measures away from being an “A” school. I knew we were going to exceed, but when I saw our students with disabilities, when I saw our Hispanic males, and I saw our African American males growing 4 and 7 points on the standardized test, I knew that we were doing some good things and that all we were going to do was add people to that puzzle and keep doing what we were doing and keep monitoring it. So the only thing we did different this year is, instead of looking at entire contents and entire grade levels, we are closely monitoring our subgroups, because we grew 99.2 percent of our students.

BARRETT: The strong results led to quick teacher buy-in and rapid expansion this year of its Opportunity Culture, or OC, teams.

SHACKLEFORD: We had such a great student outcome and teacher impact in the three grade levels where we had Opportunity Culture last year, so in year two, we went schoolwide.

BARRETT: This year, Lucama has a Multi-Classroom Leader, or MCL, for kindergarten and first grade, one for second and third, and another MCL for fifth grade, whose team also includes a master team reach teacher. One reach associate, or RA, supports the fourth- and fifth-grade teams, and another supports the second- and third-grade teams.

SHACKLEFORD: I would like to say we tripled our Opportunity Culture effect, because it was outstanding.

BARRETT: Opportunity Culture educators at Lucama all highlighted several keys to their success: strong relationships, everyone pulling in the same direction, the use of data to drive quick responses to student needs, and extensive use of small-group tutoring by all available adults.

SHACKLEFORD: Our MCLs are involved in small groups, our reach associates are involved in small groups, our tutors and interventionists who are not a part of the OC model. So outside of our core 18 teachers that we have on campus, we probably have at least 12 to 15 additional individuals that we can push in for small group. The interventionist is a district- level position that they sponsor with ESSR funds, but the tutors are—I build them into my Title I schedule. So I bring back veteran teachers who are retired to work four to five hours, four days a week and explicitly pull those Tier 3 and Tier 2 students. So they are trained teachers, they’re up to date, they go to all of our PD, they go to our district PD, and they do intense interventions every single day they are here. They do progress-monitoring, they are a part of our problem- solving PLCs—so it’s a big room of people looking at students. This year, we went a little bit different. This year I have all of my tutors skill-specific—you’re either going to be a math tutor or ELA tutor, and you are using a specific curriculum.

BARRETT: Reach associates also focus on small-group tutoring sessions.

SHACKLEFORD: For the most part, our reach associates target students all day. They don’t target our Tier 3, but they are targeting small-group reading and math, and they are targeting Tier 2 students all day. And they participate in the grade- level planning, and they rely heavily on collaborations with their MCLs—they really involve them in that conversation.

BARRETT: Lucama also pays reach associates to provide extra, short-term tutoring after school each quarter, Shackleford said.

SHACKLEFORD: We have two programs going on called “Keeping-Up Cardinals” and then we have another program called “Catching-Up Cardinals,” because we are the Lucama Cardinals. So our Keeping-Up Cardinals are students who need just a push because they may have just missed one or two concepts on our quarterly benchmarks, but our Catching-Up Cardinals are students who are missing like an entire unit, maybe on base 10 or context clues. They’re missing like an entire unit within a specific content area. So our reach associates get an additional stipend, because they stay after school for a three-week period each quarter, and they tutor those students for two days a week. Even though we exceeded growth with all of our subgroups, we saw that our exceeding was a little bit lower with our students with disabilities and our English language learners. So we have been in unit-based after-school tutoring programs, so our reach associates really work with that, too—so they target during the day, and they also target after hours too.

BARRETT: Having her reach associates provide tutoring during the day and after school creates strong relationships with students that make a noticeable difference in their learning, Shackleford said.

SHACKLEFORD: I think the relationship is very, very important, because, number one, those RAs are in those classrooms every single day, and the tutors are dealing with those students, so they know when to push, and they know when to pull back. If you’re tutored by someone, they're going to be the ones that give you your separate setting benchmark.

People that you’ve already built a relationship, people that you are already comfortable with, they know your mannerism, they know your learning behaviors, they know when you’re off, so they quickly tell me, “Can we start this testing session 30 minutes later, because so-and-so is not performing or acting the way we should?” So relationship is very important.

BARRETT: Across North Carolina, teachers are implementing instruction based on the science of reading, as required by state law, with training they received through LETRS, or Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling. When the law passed requiring that instruction be grounded in the science of reading, North Carolina educators expressed concern about the lack of in-school coaches and ongoing professional development for teachers.1 But at Lucama, MCLs provide precisely the coaching and on-the-job PD that their team teachers need.

SHACKLEFORD: Our MCLs are like our train the trainers. Our MCLs are going to these districtwide professional developments—so they’re getting the science, and they are our building-level support for the roll-out and the implementation and overseeing that. They’re having the conversations about the bridging-the-gap activities that teachers have to do, and they are having the conversations to make sure that our teachers are pacing themselves along the way.

BARRETT: The curriculum the school had used did not cover everything students needed for all the components of science of reading-based instruction, Shackleford said. Teachers in grades three through five were focused on vocabulary, but they knew that their students were lacking fluency and decoding skills.

SHACKLEFORD: So as we were going through LETRS training, the teachers realized that they had to do a shift in teaching. It was beautiful because our third-, fourth-, and fifth-grade teachers bought into it. They were like, “Oh, that’s why we can’t attack this passage, because we don’t have this!” So now our teachers, every single day within that 120-minutes to 150-minutes ELA block, they are teaching 20 to 30 minutes of explicit, core phonics or phonemic awareness or vocabulary instruction, and we monitor that data piece every nine weeks, because what we are doing is we set measurable outcomes. At the end of this six-to-eight-week period, we want 80 percent of our students to be able to have these phonics and phonemic awareness of vocabulary skills. Those students that do not get it, they get an additional dip of that core phonics or phonemic awareness with a tutor. So K–2 teachers are just happy that they have a common curriculum, and that we are going to have vertical PLCs that say, “This is where you need to start next year.

This is where we didn’t get it.” And we’re actually looking at real problems. There is a decoding problem, there is a fluency problem, there’s a comprehension problem. So I just think science of reading has come alive.

BARRETT: MCL Laura Pittman said that as her team has realized what phonics pieces their fourth- and fifth-graders were missing, they have worked together to look closely at the data and determine how to get students what they need.

PITTMAN: We are working as a team and planning and coming back with data with how our students are doing, and that was one of the data pieces, you know. They are learning these syllables—they can tell you this is a closed syllable, they can tell you how to pronounce it—but then, when they go to write the word, they’re still not writing the words correctly, or they’re still not being able to read these words. So it’s, “OK, we need more application, so what can we do to get that?” So it’s a work in progress, and we’re just working with the data we’re getting from the students and trying to change it that way.

BARRETT: Between the vertical planning, focus on data from the beginning of the year to determine those most in need, and small-group instruction led by MCL Pittman, Reach Associate Joy Mosley, and others, students soared, Pittman said.

PITTMAN: These students grew leaps and bounds. I was pulling them, Ms. Moseley was pulling them, and then, we had a couple of other people pulling, and we just saw lots of growth. What has changed is we have more people available to pull groups and to look at the data, and we’re looking at it more as a team together. So it’s a lot of collaboration.

BARRETT: Macey Williams, the master team reach teacher for fourth grade, appreciates how much time they have now for that collaboration.

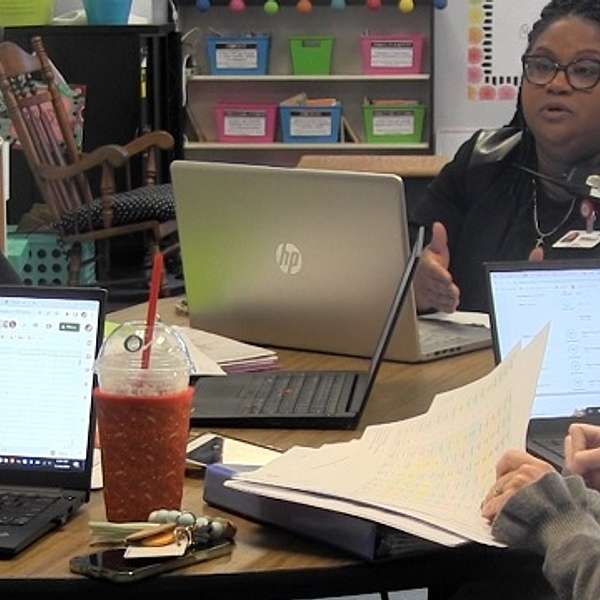

WILLIAMS: Lucama has always looked at the data, but we didn’t necessarily always have the time to go back and implement it with fidelity the way we wanted to. But now, with our data days that we have, after every quarterly benchmark we have time during that day to plan out, “OK, this is our data, this is what we see we need, now this is how we’re going to address it, and these are the materials we are going to use.” So it gives us more planning time, where in the past, the teachers at Lucama have always met together, even if it’s like sitting at lunch, “Oh, mine did this, mine did this, mine were weak on this.” But we never have had that time to really sit down and implement it the way that we would like to. We’d pull our groups in our own classrooms, but it’s been much more beneficial to be able to say, “OK, now here is our plan, and now we can put it into action.”

BARRETT: Master team reach teachers typically both reach more students and assist with team leadership, so this year, Williams is coaching a brand-new teacher.

WILLIAMS: I’ve always had mentees—I've been a mentor for many teachers throughout the years, and I think the difference with being an OC master team reach teacher with her has been the chance for me to go into her classroom more and to give her more time and more attention—and I haven’t had the time before to go into the classrooms with them and kind of show them and model for them, just so they can learn from my experience.

BARRETT: Joy Mosley, the reach associate supporting the fourth- and fifth-grade teams, has noticed a big impact coming from the focus on science of reading in her small groups. For example, she had one group focused on reading comprehension.

MOSLEY: We knew that just from the get-go, these kids coming out needed some comprehension. They were able to place out of that group and to move forward—so therefore, I can focus on going to the next step with them. I’ve seen a change in the school just over seven years of a lot of the kids. They want more, they want to do more, because they see that we want more for them.

BARRETT: This higher motivation was one improvement that many educators at Lucama highlighted.

MOSLEY: I think, just our whole team, like, we all are on the same page with everything. When you have a team that wants all—we're here, we’re 100 percent, we’re going to do what we have to do—it makes a difference with the kids to me. This role is fantastic for me because I’m able to get my hands into so many classrooms, into so many different things—I'm into science, I’m into math, I’m into ELA, like it’s not just one thing—and it’s among many children. I’m able to reach many children, I’m able to get to know many children, to build those relationships.

BARRETT: Williams agreed that student motivation and relationships are both proving crucial.

WILLIAMS: The motivation has really improved with some of the students that I’ve seen. And the relationship thing is big. I know there are other students that are in the other teacher's classroom that I don’t teach specifically, but I have pulled for small-group instruction, and they’ll come to me in the hall and give me a hug. We had one the other day that was having a rough morning and did not want to leave the classroom when it was time to go to specials, and the other teacher said, “you know, he doesn’t want to leave the room.” So she took my class and dropped them off, and I sat with him for a minute, and got it together. The rest of the day, every time he saw me, he would come up and give me a hug. He was here the rest of the day, and he was no longer of that mindset that he wanted to go home. So we can build those relationships even in the few minutes that we do see them if we pull them in small groups. I do think that with the Opportunity Culture and all of the people who have hands-on-decks with the students, I think, the students feel like they are really important.

BARRETT: Thank you to all the educators at Lucama who shared their experiences with us. For more about Wilson County Schools, keep an eye on OpportunityCulture.org for short video clips of their educators in action.

----